The Crane Wife by Patrick Ness

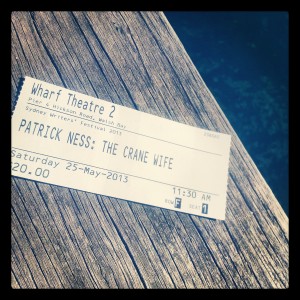

“Most fairy tales begin with an act of cruelty; gingerbread houses, someone abandons a child in the forest or whatever, but this one begins with an act of kindness — a man saving a swan.” Patrick Ness said of his latest novel The Crane Wife at the Sydney Writers’ Festival on the 25th of May.

“Most fairy tales begin with an act of cruelty; gingerbread houses, someone abandons a child in the forest or whatever, but this one begins with an act of kindness — a man saving a swan.” Patrick Ness said of his latest novel The Crane Wife at the Sydney Writers’ Festival on the 25th of May.

Kindness is among many reoccurring themes in The Crane Wife, which Ness described at the festival as a “fantasia” based on a Japanese folk tale that he was introduced to as a child. In Ness’ tale, George, a mild-natured, 40-something divorcee, is drawn out of his bed in the middle of the night by a keening sound, that “tore at his heart like a dream gone wrong, a wordless cry for help that almost instantly made him feel inadequate to the task, helpless to save whatever was in danger, pointless even to try.”

But try he did, racing out into his back garden half dressed, to find a magnificent crane with an arrow shot through its wing. He helps it — it flies off. As this seems a somewhat an unlikely occurrence in a small back garden located in the outer suburbs of London, everyone George tries to tell about the crane suspects he dreamt it.

George goes back to his life managing a printing shop and amusing himself by making small, artistic cuttings out of old book covers. Until the striking, mysterious Kumiko enters his shop one day, and they begin a relationship.

As an artist, Kumiko collaborates with George by fusing his book cover cuttings with her elaborate artworks made of fine white feathers. Together they begin to make quite a lot of money.

Kumiko has an almost magical presence, even George’s daughter Amanda is somewhat mystified by her, though she is uncertain of the speed at which Kumiko and George’s relationship seems to be moving.

George is close to his daughter Amanda, who at the festival Ness described as “kind without being nice, which is so interesting to me.”

Amanda has a hard time connecting with others, mostly due to a tendency to say the wrong thing at the worst moment, and what George describes as a “slash and burn” approach to trying to find herself as she moves through life. I found Amanda to be a fantastic character; frustrating, heart-jerking but very real.

As time continues to pass, Kumiko remains mysterious, and George becomes greedy for more knowledge of her. He wants to be able to place her, he is upset by the idea that there seems to be so much more for him to learn about her, and she is evasive about her past, laughing: “’I do not like talking of myself so much. Let it be enough that I have lived and changed and been changed. Just like everyone else.’”

The story is interspersed with another tale of a crane and a volcano in love, and the destruction that their love brings.

When he spoke at the festival last weekend, Ness said:

“When you fall in love you’re writing a story about someone and hoping they’re writing the same story about you.” Ness concerns himself with truth, stories and perspective heavily in this tale-within-a-tale, in which Kumiko explains to George: “’…Stories do not explain. They seem to, but all they provide is a starting point. A story never ends at the end. There is always after. And even within itself, even by saying that this version is the right one, it suggests other versions, versions that exist in parallel. No, a story is not an explanation, it is a net, a net through which the truth flows. The net catches some of the truth, but not all, never all, only enough so that we can live with the extraordinary without it killing us.’”

But George cannot bring himself to be satisfied with the story, to merely live with the extraordinary. The result is a tragic and moving, in this intricate novel that concerns itself with what it is to love, and how knowledge, power, possession and kindness interconnect with it.

Links:

Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy

Having gorged myself on a literary diet of predominately young adult and vampire fiction for the past few months, last week I felt it was time for another classic. I’ve always wanted to read Tess of the D’Urbervilles and was lusting after the pictured new penguin classics hardcover edition, so I settled on it. Hardy’s gorgeous writing, tragic heroine and moving story did not disappoint.

Having gorged myself on a literary diet of predominately young adult and vampire fiction for the past few months, last week I felt it was time for another classic. I’ve always wanted to read Tess of the D’Urbervilles and was lusting after the pictured new penguin classics hardcover edition, so I settled on it. Hardy’s gorgeous writing, tragic heroine and moving story did not disappoint.

All I’d ever heard about the plot of Tess of the D’Urbervilles was that involves a rape, and I assumed wrongly that this was to be the crux of the story. Tess of the D’Urbervilles opens on John Durbeyfield’s discovery that, despite his current poor state, his ancestors were the D’Urbervilles, who are descendants of one of the Knight of The Royal Oak, and that Durbeyfield is a corruption of this grand name. He informs his family and, following a tragic event further depleting the Derbeyfield’s income, his wife hatches a scheme to send his daughter Tess to a nearby rich branch of D’Urbervilles to claim kinship and hope for help in forging an advantageous marriage. In doing so Tess is put at the mercy of the abhorrently amoral Alec D’Urberville, who takes advantage of her situation and forces himself upon her, obliterating her maidenhood and perhaps any chance she had of happiness in her conventional society.

Challenging conventional values is a major concern of Hardy’s and he uses Tess’ fall to call them into question. The following passage conveys both this theme and the rich writing he utilises to convey it:

“A wet day was the expression of irremediable grief at her weakness in the mind of some vague ethical being whom she could not class definitely as the God of her childhood, and could not comprehend as any other. But this encompassment of her own characterisation, based on shreds of convention, peopled by phantoms and voices antipathetic to her, was a sorry and mistaken creation of Tess’ fancy – a cloud of moral hobgoblins by which she was terrified without reason. It was they that were out of harmony with the actual world, not she. Walking among the sleeping birds in the hedges, watching the skipping rabbits on a moonlit warren, or standing under a pheasant-laden bough, she looked upon herself as a figure of Guilt intruding into the haunts of Innocence. But all the while she was making a distinction where there was no difference. Feeling herself in antagonism she was quite in accord. She had been made to break a necessary social law, but no law known to the environment in which she fancied herself such an anomaly.”

Years pass and eventually Tess takes a position as a milkmaid at Talbothays Diary, set in a luscious part of the country side. There she finds relative mental peace, until attraction blooms between her and Angel Clare, a pastor’s son learning the art of farming. Hardy’s descriptions of the settings in the narrative are always artful, but never more than at Talbothays Dairy, where he mingles love with milking cows, leafy green trees, vast pastures and the hum of nature. Here are two of my favourite passages from the section:

“They met continually; they could not help it. They met daily between that strange and solemn interval, the twilight of the morning, in the violet or pink dawn; for it was necessary to rise early, so very early here. Milking was done betimes; and before the milking came the skimming, which began at a little past three… The gray half-tones of daybreak are not the gray half-tones of the day’s close, though the degrees of their shade may be the same. In the twilight of the morning light seems active, darkness passive; in the twilight of the evening it is the darkness which is active and crescent, and the light which is the drowsy reverse. Being so often – possibly not always by chance – the first two persons to get up in the dairy-house, they seemed to themselves the first persons up of all the world. In these early days of her residence here Tess did not skim, going outside at once after rising, where he was generally awaiting her. The spectral, half-compounded, aqueous light which pervaded the open mead, impressed them with a feeling of isolation, as if they were Adam and Eve.”

“How very loveable her face was to him. Yet there was nothing ethereal about it; all was real vitality, real warmth, real incarnation. And it was in her mouth that this culminated. Eyes almost as deep and speaking he had seen before, and cheeks perhaps as fair; brows as arched, a chin and throat almost as shapely; her mouth he had seen nothing to equal on the face of the earth. To a young man with the least fire in him that little upward lift in the middle of her red top lip was distracting, infatuating, maddening. He had never before seen a woman’s teeth and lips which forced upon his mind with such a persistent iteration the old Elizabethan simile of roses filed with snow. Perfect, he, as a lover, might have called them off-hand. But no – they were not perfect. And it was the touch of the imperfect upon the would-be perfect that gave the sweetness, because it was that which gave the humanity.

But how will Tess’ past affect Angel’s feelings? Should she tell him of her violation at the hands of D’Urberville?

Recent Comments